|

This blog post is based on a conversation between me (Suzanne Elvidge, freelance writer and journalist at Peak Words) and the #CoffeeBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Book to join #CoffeeBuddies on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 2.30 pm BST (GMT+1 hr) at Eventbrite.

News outlets, including print and online media, have not had a good reputation for reporting breakthroughs in science and medicine:

Why it's important to get science into the media There are two key audiences for science and research in news media; the general population, and pharma industry personnel. Unless they have a particular interest in science, lay people are often looking to find out how breakthroughs in science and medicine will affect their health and that of their families or friends. News in the mainstream media, in print or online is a way to educate people about the scientific process, how research really works, and how long drug development actually takes. And this has never been more important than during the Covid-19 pandemic. Business development teams and management at C-suite level in the biopharma industry use the media, including specialist news publications and sites, and trade publications, to find out about new approaches, breakthroughs, technologies and techniques, and find collaborators. Investors use similar sources to see who needs funding and who could provide a return on investment. Talking to the press Good media coverage of research does depend on how the science is communicated by the scientists – it is the responsibility of both the scientist and the journalist. This means the interaction between the scientist and the journalist is very important. Start by knowing both of the audiences – the journalist's level of knowledge, and the readers' knowledge and needs. Not all news stories are written by science writers, and not all science or health writers have a science background. Conversations and press releases need to be in the right language for the audience, in plain English without hyperbole, and without too much 'science speak' for a non-science audience. It's important for scientists to speak on a level that people can understand - using jargon or high science terms can make the conversation complex and isn't worthwhile for the reporter or their audience – Lisa LaMotta, Editor-in-Chief, Risk & Regulatory Thought Leadership at PwC. Journalists are busy people – those who are working for online daily news publications may be putting out anything from three to five or more stories a day. A good press release will increase the chance of getting a story noticed and published. Presented with a pitch or press release, the journalist will pick the one that is well written, contains good information, answers the right questions and includes feasible quotes over and above the one that is just PR fluff and insubstantial, generic quotes. Don't keep on calling journalists to see if they have received your press release, unless there is a good chance that it has gone astray, or there is something useful to add. Hints and tips for a good release:

Tracking a piece of science research gives an idea of how different outlets report science, and where they get their information. The original paper The original paper, 'Padeliporfin vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy versus active surveillance in men with low-risk prostate cancer', was published in The Lancet Oncology. This paper compared vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy, derived from a sea-dwelling bacterium, with standard-of-care (watchful waiting) in men with low-risk prostate cancer and suggested that it was safe and effective and could defer or avoid more radical therapy. The press release The press release, entitled ' Light therapy effectively treats early prostate cancer', came from University College London. It's written in user-friendly language, and its statements and conclusions are much more definitive than those in the original paper. It also provides an image and some links. Medical press The pieces in the Urology Times and Cancer Therapy Advisor both target physicians. They both use non-sensational language, and their conclusions are cautious, couched in a scientific and medical perspective. The key differences are that the Urology Times uses the press release as the source, including quotes, whereas the Prostate Cancer Advisor relies more on the original paper. To provide validation, the Prostate Cancer Advisor includes a perspective from a physician not included in the study. Popular science press IFL Science's approach to the story uses lay language but does not dumb down the story, and also uses some information from the press release to shape the piece. It pulls in background information to expand on the topic. Importantly, it says that the drug is not yet approved – this is from the press release and is vital in managing readers' expectations. The conclusion is positive, but the language remains measured The newspapers Newspaper coverage of science can be sensationalist, including titles with phrases such as: 'Researchers were shocked by results', 'Miracle drug', 'Results are astonishing', 'Blockbuster' or 'Cure'. The Telegraph's piece (now behind a paywall) emphasises 'complete remission for half of patients' in the title. The Daily Mail, a newspaper fond of capital letters, says that the 'bacteria… will kill prostate cancer in HALF of all patients'. The Sun (a paper with a strong male readership) highlights in its title that the treatment won't leave men impotent. Both The Sun and The Telegraph mention that the treatment isn't approved yet. As many newspaper stories leave people clamouring for a treatment that may be years away from approval, this confirms how important it is to include these details in the press release. The story in all three newspapers is shaped very strongly by the press release. Each article has pulled in information from UK cancer charities to provide additional information for the readers; this also provides validation for the piece. Learnings from the analysis

0 Comments

A preprint of a study released earlier this week has confirmed the increased risk of hospital death in people of south Asian backgrounds with Covid-19, and has started a look into the reasons why. Since the early days of the Covid-19 outbreak, there have been reports of higher levels of deaths in people of colour. A Public Health England report looked into the links between ethnicity and outcomes of Covid-19, and showed that the risk of death is higher in people from black and Asian ethnic groups compared with white people. The ISARIC CCP-UK Prospective Observational Cohort Study of Hospitalised Patients looked at data from 30,693 people admitted to 260 hospitals in England, Scotland and Wales between February and May 2020. There was no difference in severity of illness on admission. While just 5% of the people admitted had ethnicity reported as south Asian, people from this cohort were 19% more likely to die than white patients. People from all ethnic minorities were also more likely to need intensive care. The increased rate of diabetes in the south Asian patient cohort compared with the white patients (40% vs 25%) could explain (at least in part) the increased risk of death. Type 2 diabetes has links with increased risk of death in hospital in people with Covid-19. In May 2020, an NHS England report showed that of the 23,804 people who had died in hospital as a result of a coronavirus infection, almost a third had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. When in hospital with Covid-19, people with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to die than people who don't have diabetes. The implications of the ISARIC CCP-UK study, as discussed by the authors, are that ethnicity should be accounted for in decisions about prevention, treatment and vaccination, and any disease-related guidance and policies should be developed with an awareness of the high percentage of south Asians in public-facing and key worker roles.  This blog post is based on a conversation between Ian Rees, Unit Manager Inspectorate Strategy and Innovation at the MHRA and the #CoffeeBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Book to join #CoffeeBuddies on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 2.30 pm BST (GMT+1 hr) at Eventbrite. The core principle of the Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is to ensure that medicines, medical devices and blood components for transfusion are safe, of an appropriate quality, effective, and can be manufactured consistently. The MHRA is made up of three centres:

The MHRA needs to do what is appropriate with each individual project, and to achieve this, works in collaboration with a range of organisations along the development pathway to create as integrated a programme as possible:

From an international perspective, the MHRA also works with:

Supporting innovation The MHRA provides advice at any stage of development across the whole of the drug development lifecycle, and according to Rees, the earlier the developers request the advice, the better. The MHRA innovation office works with companies, research institutions, consortia and hospitals as they make the step from the bench to the bedside (the discovery and preclinical steps in translational medicine). This support includes innovations in drug and device development and in manufacturing processes. The innovation office also carries out horizon-scanning activities, keeping the MHRA as a whole up-to-date on emerging technologies, medicines and devices. The inspection and assessments office then covers the stages from preclinical to market. One of the important roles of the innovation office is to provide confidential and informal expert regulatory information, advice and guidance, allowing inventors to begin to access the inspection pathway and engagement process. This free advice leads into the more formal scientific advice meetings and interim inspections. The MHRA also works with NICE to provide joint scientific advice to create clinical trials that could support and even accelerate adoption. Companies and institutions developing innovative medicines for life threatening or seriously debilitating conditions with clear unmet medical need may also be able to access the early access to medicines scheme (EAMS). This allows patients to access drugs before marketing authorisation. The innovation office was launched in 2013, and since then has dealt with more than a thousand enquiries and facilitated over 150 meetings. However, these have mostly been with research institutions and small and medium enterprises (SMEs); big pharma companies seem to be less interested in discussion. This can lead to delays – for example, a big pharma company wanted to move from batch to continuous manufacturing, but it took almost two years for the company to release a polished version of the documentation to the MHRA. Had this been provided at an earlier stage, the 'polishing' could have been carried out in parallel with the discussions, meaning the manufacturing could have begun up to 18 months earlier. The impact of Covid-19 The coronavirus pandemic and the drive for new vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics is changing perceptions of what is possible in data gathering and product approval. The push to move products into clinical trials quickly has compelled developers and regulators to discuss projects and seek scientific advice. The MHRA is able to prioritise and support Covid-19 research, and has procedures in place for rapid scientific advice, reviews and approval. Examples of projects that have been able to move faster under the pandemic conditions include the convalescent plasma programme, the approval of the use of remdesevir in certain patient populations under EAMS, and the approval of the Covid-19 Oxford Vaccine Trial in seven working days. MHRA post-Brexit The shape of the existing UK regulatory pathways won't change in a post-Brexit world, but what is not yet clear is whether regulatory approvals will remain linked with EMA, or the MHRA will act as a standalone regulator. The MHRA's guidance updated in February 2020 states that the UK can only act as a concerned member state (CMS) in decentralised procedures or mutual recognition procedures until the end of the transition period. There is still so much uncertainty at the moment, but the aim post-Brexit is for a better-integrated pathway that brings in other agencies in parallel. It is possible that the MHRA could reduce in importance compared with the Asian and US regulatory agencies, as the UK is no longer the gateway to Europe. However, working in partnership with individual or groups of regulatory authorities could make the MHRA work faster, and be more responsive, innovative and flexible. This would require managing the balance between science and risk. This blog post is based on a conversation between Andrew Papanikitas, Senior Clinical Researcher at the University of Oxford Department of Primary Care Health Sciences and the #MotivationBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Book to join #MotivationBuddies and #CoffeeBuddies on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 2.30 pm BST (GMT+1 hr) at Eventbrite.  In discussions about ethical and moral issues, the world is full of opposing viewpoints, never more so than in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic and the aftermath of the George Floyd killing. The best and most fruitful discussions are based around respectful disagreement, which seeks to understand why someone thinks how they do and prioritises logic and facts over opinion in the response. Building a consensus framework for medical ethics, particularly in troubled times, needs this kind of reasoned respectful disagreement. Medical ethics isn't always about consensus though. It can be about a single voice speaking up against the status quo. The issues and skills learned and discussed in medical ethics are not just relevant in healthcare they are widely applicable anywhere. Ethics: the personal perspective Our personal ethics can be driven by our goals, beliefs and values, and by the conditions in which we find ourselves, and all of these can influence communication and clinical practice.

Ethics: Coming to consensus When people understand why they are doing something, and are supplied with principles, structures and processes, they are more likely to comply. Medical ethics frameworks, created through discussion and consensus, should therefore include:

The framework should be applicable to healthcare professionals across the range of professions and agencies, but it should consider different people and perspectives. If guidelines are created for individual groups, care needs to be taken where the sets of people cross over, for example the two sets of guidelines for midwives and obstetricians working with pregnant individuals, or the many different guidelines for the range of healthcare professionals working with older people in care homes. Ethics, empathy and connection Feelings of compassion (the desire to alleviate suffering) are important for healthcare professionals. In order to cope, and to be able to make decisions, it is important to mix in logic and reason, but this can result in healthcare professionals taking too big a step back, and healthcare becoming too dehumanised. Empathy (feeling what others feel), can play an important role by allowing healthcare professionals to: develop a two-way relationship with patients; gain insight into their condition and mindset; step into their shoes; respect their dignity; and base their care on the understanding gained.  This is a personal as well as a scientific blog, and as such is being posted on both my websites. My BMI currently puts me into the obese category. I have often said that I don't have an issue with food – I just like it too much. I may be fit and obese, running half marathons, but I can still be damaging my joints and my heart, and risking type 2 diabetes. But now, in the time of Covid-19, obesity puts me at a higher risk than the rest of the population should I become infected. How big is the risk? In patients under 60, obesity is a risk factor for hospital admission. In a US study, patients with a BMI of 30-34 were around twice as likely to be admitted to acute or critical care, compared with those with a BMI of less than 30. In patients with a BMI of over 35, the likelihood of being admitted to acute or critical care rose by 2.2-fold and 3.6-fold, respectively. Higher numbers of obese patients require invasive mechanical ventilation. The OpenSAFELY collaborative carried out a review of electronic medical records of patients in England. According to the results, having a BMI of between 30 and 35 (obese) increases the risk of hospital death by 1.3-fold. This climbs to 1.6-fold for a BMI of 35-40, and a BMI of greater than 40 (morbidly obese) more than doubles the risk of death (2.3-fold). Because the science is moving so quickly, this preprint has not yet been finalised or assessed by experts (peer-reviewed). The science behind the difference Being overweight generally makes it harder to breathe, and is known to be a risk factor in respiratory diseases such as asthma, sleep apnoea, acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. There are a number of theories behind the increased risk of more severe illness and death related to Covid-19 in people who are obese:

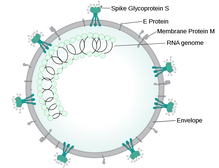

Looking at the futureMy weight has gone up and down over the years. My biggest gains were in my thirties, and I lost three stone before I got married in 2009, giving me a BMI of 24. During my marriage and following bereavement, the weight went right back on. But it's not just me. The most recent Health Survey for England (2018) found that 67% of men, 60% of women and 28% of children were overweight or obese. As SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is likely to stick around for some time to come, tackling obesity is going to be important. As part of COUCH Health's mission to improve 1 million lives by 2022, I have pledged to lose weight as part of a challenge alongside my friend and medcomms colleague, Ash Rishi. It has been up and down during the lockdown, but I'm going to try again, driven by the excess risk of Covid-19, using the evidence-based and NHS-backed Low Carb Program. This blog post is based on a conversation between Michel de Baar, Executive Director, BD&L - Infectious- and Cardiometabolic Diseases, Vaccines & Immunology at MSD (Merck & Co. Inc) and the #CoffeeBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Book to join #CoffeeBuddies on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 2.30 pm BST (GMT+1 hr) at Eventbrite.  Business development teams looking to fill pharma company pipelines are seeking products that meet unmet medical needs, either filling gaps where there are no existing treatments, or creating a product that is significantly better than something already on the market. These opportunities should come with solid science and at least the beginning of a good data package created using studies with the right models and the right controls. As discussed in an earlier #CoffeeBuddies session, investments pre-Covid-19 had started to move to earlier stage projects, and this needs companies to reach out actively to universities and biotechs that have assets based on good science that might otherwise slip under the radar. This can be helped by good local, national, and international networks created through links with national and local trade organisations, and local academia. Operating companies in individual territories may be able to provide information on local research via their networks, and even keep an eye open for ideas. By building relationships with biotechs and academia even before they have something to licence, companies can get an early 'foot in the door'. They can ensure that the science is good as well, by mentoring and supporting the SMEs and institutions as they develop their data packages. In order to pick the right projects, business development and licensing teams need to remain objective. Working together can help to reduce any natural bias, and can also provide subject matter and technology expertise. Working without a 'shopping list' means that projects can be picked up opportunistically, potentially creating a whole new franchise. Combatting Covid-19 SARS-CoV-2 is a virus that is potentially fatal, and increasing evidence suggests that it could have longer-term effects for some people. This threat is providing a driver for business development teams to find and partner for generic and innovative drugs that could help. The urgency means that some companies are making announcements at the statement of interest stage, even before full agreements are in place. It will be interesting to see if this remains after the crisis is over. Before the outbreak, MSD's pipeline already included research key to the area of Covid-19 infection – infectious disease, vaccines, immunology and respiratory disease. After the outbreak, the company switched almost all of its efforts to respond to the Covid-19 outbreak The business development teams, the global competitive intelligence group and the discovery teams have worked together to evaluate around 250 different targets and programs with early stage data packages. Assessment of potential assets is ongoing. This includes screening of existing drugs for new activity, which could potentially speed up drug development. MSD's response to Covid-19 includes a number of vaccine projects. Deciding which will go forward will depend on further understanding of the immunology of the virus, and the manufacturability, safety and immunogenicity of the different candidate vaccines. The most appropriate type of vaccine for the prevention of Covid-19 isn't yet clear, and companies around the world are taking a number of different tactics, as a previous #CoffeeBuddies session talked about. These include viral vectored and nucleic acid vaccines, which are still new approaches and may prove challenging for approval and scale-up; inactivated and protein subunit vaccines, which are tried and tested but can be complex to manufacture and often need a booster; and live-attenuated vaccines, which produce a strong immune response but may be associated with risks. Controlling the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus may require a lower risk vaccine and boosters to develop herd immunity, along with ring vaccination with a shot that produces a faster response but with a slightly higher risk of side effects. What will the pandemic mean for investors While the pandemic is ongoing, companies focusing on Covid-19 prevention and treatment are unlikely to make much of a profit; any marketed drugs, especially vaccines will need to be distributed widely and provided cost-effectively to those at highest risk. This means that long term investment will be needed, with an extended period until return on investment – both companies and shareholders will need to be patient. The future: the 'new normal? The biopharma industry is currently very much focused on vaccines, virology, immunology, and infectious diseases, which haven't been 'fashionable' areas of research. However, it's likely that there will be a shift back into 'normal' ways of working, with the focus returning to therapeutic areas with a higher potential return on investment, such as oncology and cardiovascular disease. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed