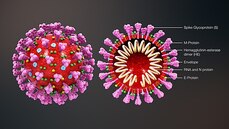

This blog post is based on a conversation between Michael Watson, CEO of MEVOX and ex-president of Valera, Moderna's infectious disease spin-out, and the #CoffeeBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Book to join #CoffeeBuddies on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 2.30 pm BST (GMT+1 hr) at Eventbrite. Since the first reported cases of a mysterious outbreak of viral pneumonia in Wuhan, China, in late December, the virus, now called SARS-CoV-2, hasn't been out of the news. Human to human transmission of the infection, known as Covid-19, was confirmed on 20 January 2020. As of 7 May 2020, there had been 3,843,153 reported cases and 265,657 reported deaths worldwide. The UK's daily confirmed Covid-19 deaths per million (rolling 7-day average) peaked at 13.89 per million on 15 April 2020, and had fallen to 8.37 per million on 7 May 2020. All about the virus Coronaviruses (from corona, Latin for crown or wreath) are RNA viruses with spike proteins studded all over their surface. Evolving alongside the amniotes (reptiles, birds and mammals), coronaviruses and have been around for millions of years. Coronaviruses were first identified in the 1960s, and SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans. A number of coronaviruses, including B814, 229E and OC43, cause around 15% of common colds. While the new virus' origin is still not clear, it appears to be closely related to bat and pangolin viruses. There have been a number of coronavirus outbreaks over the last two decades, including the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV-1) outbreak in China and Hong Kong in 2003, and the MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV) in 2012. The pandemic in 1889-1890, which resulted in one million deaths, may have been caused by HCoV-OC43 jumping from cows to humans. SARS-CoV-2's spike proteins bind with the human ACE2 receptor, found in lungs, kidney, heart and gut. This ties in with the symptoms of Covid-19, which include fever, cough, shortness of breath, and diarrhoea, and can worsen to cause strokes and kidney failure. Letting go of the tiger's tail Modelling from Neil Ferguson and the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team suggested that, if nothing was done to mitigate the epidemic in the UK, critical care bed capacity would be exceeded in the second week of April, and deaths would peak at around 500,000 in May or June. Controlling the tiger that is Covid-19 requires primary and secondary prevention, allied with primary and secondary treatment approaches:

The UK went into lockdown on 23 March 2020. The UK government is discussing when and how lockdown will ease, and what social intervention will look like in the future. Between the current peak and a potential secondary peak of infection as lockdown eases is a critical and narrow window for vaccine and therapeutic development. Highly effective contact tracing and case isolation could also be important in controlling new outbreaks. Antivirals could play a role in treatment A study of Gilead's remdesivir in 1063 hospitalized adults showed a 31% faster time to recovery in treated patients compared with placebo (p<0.001), reducing the median time for recovery to 11 days compared with 15 days. The mortality rate in treated patients was 8.0% compared with 11.6% in the placebo group (p=0.059). Remdesivir has been studied in Ebola virus disease, MERS and SARS caused by SARS-CoV-1 infection. Designing a vaccine for primary prevention A safe and effective vaccine will be the best way out of the current pandemic, as waiting for herd immunity would require between 60% and 80% infection in the population, with a lot of suffering and death over several years. There are over 125 Covid-19 vaccine candidates in the pipeline to date, with eight or nine in the clinic. This is expected to increase to over 25 in the clinic by the end of 2020. Approaches include nucleic acid vaccines (mRNA, DNA),inactivated or live attenuated vaccines, or viral vectored vaccines. Normally vaccine development takes over 10 years, but this outbreak has seen vaccines developed to clinical stage in record time. Each vaccine approach has its benefits and its challenges:

Another positive for the development of a vaccine – while coronaviruses do continue to mutate, they have an RNA 'proofreading machine' that slows the evolution of the virus. According to data published on 4 May 2020, there have been relatively few mutations spotted to date. Provided clinical trials can show a 'good enough' protection from an initial dose, or dose + booster, the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may need to be given annually, much like the influenza vaccine.

1 Comment

Graham Combe

7/5/2020 04:01:18 pm

Fantastic write up again Suzanne, great work!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed