. This blog post is based on a conversation between Musaddiq Khan, Director, Clinical Program Operations at Eli Lilly and the #CoffeeBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Book to join #CoffeeBuddies on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 2.30 pm BST (GMT+1 hr) at Eventbrite.

Clinical programs operations teams focus on the efficient delivery of clinical trials, with time and data quality as the metrics of success. The impact of the Covid-19 outbreak on clinical development The current pandemic, and the different states of lockdown around the world, have had differing effects on clinical development, dependent on the area of research. Companies working on vaccines and therapeutics for SARS CoV-2 infections have had access to greater funding. They have also seen communications barriers coming down, allowing companies and research organisations to be able to engage more quickly and more directly with regulators. By changing the priorities within pipelines, pausing non-Covid-19 clinical trials, and putting new projects on hold, companies have been able to focus people and resources on pandemic research. Companies working outside the field will also have had to cancel projects and put them on hold. For all of these, as the world moves forward, there will be a need for a second round of pipeline prioritisation, particularly in the light of the warnings of global recession. During the outbreak, clinical trials may be smaller and quicker, with different stages running in parallel. However, it will be important to maintain the balance of data and speed to keep the confidence of health care professionals and patients. A positive sign of the desire from the general population to do what it can about the virus is the response to the WHO's conditional backing of challenge studies for a Covid-19 vaccine. As of 21 May 2020, more than 24,000 people in the US have signed up to volunteer for challenge studies. Making the most of the energy in the industry The urgency to get a treatment or prophylactic for the coronavirus infection has led to heightened energy across the industry, but for individuals, maintaining this level of energy may be hard long term. For some, working from home and meeting via video calling, and so not commuting helps them. For others, however, who have caring responsibilities, are shielding or who find Zoom calling exhausting it can be more challenging. Understanding people's motivations and stress points can help to manage the situation. It is hard to create and maintain the same kind of urgency for chronic disease, perhaps because the coronavirus affects everyone, but chronic diseases, especially the rarer ones, are less in the spotlight. Getting back to work Companies looking to get back to work will have to face a number of challenges. Some groups of people, such as lab staff, will find it hard to work from home, and may have to work shifts to get around social distancing. Where the pandemic has forced companies to close clinical sites, management will need to work out how studies can be restarted, for example ensuring the integrity of data. Into the future Moving forward, companies will have to reassess how clinical trials are carried out. One approach is to carry out decentralised clinical trials taking the study to the patient, rather than the patient to the site. Virtual clinical trials may use apps, devices, and wearable monitors, have local points where participants can drop off clinical samples, or have nurses doing clinical trial home visits. Hybrid studies include some site visits and some remote monitoring. The pandemic could be the catalyst to normalise decentralised trials, and the pharma industry and CROs need to be ready. The levels of energy in the industry, and the levels of trust from the public, will depend on the success of any preventive or therapeutic approaches. It will be interesting to see how many of the current changes remain in place once the sense of urgency falls. Things from this time that it would be good to hold onto include:

0 Comments

This blog post is based on a conversation between Kat Arney, founder of First Create The Media, Peter Penny, life and career mentor, and the #CommunicationBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Telling stories to each other is a key part of what makes us human. Stories help us make sense of the world, put things in order in our own heads and the heads of our listeners, and aid us in thinking about the form of our lives. Telling stories isn't just personal though – stories play an important role in science and business communication, from explaining concepts to pitching for projects and funding. The importance of story in comms: Boring comms waste lives Communicating ideas in story form can stop presentations from being mind-numbing, and become more than just lists of facts or milestones. Boring communications waste lives, by frittering away the listener or reader's precious time. They also allow important ideas that could impact wellbeing, lives and health to slip by unnoticed. The ordered structure of a story not only helps the listener but also works as a cognitive tool to help the teller order their ideas. Building the story As in fiction and drama, comms stories have a beginning, a middle and an end. They draw the listeners in and make them want to know what happens next. Good comms stories use characters – patients, diseases, drugs, researchers – and show what happens to them. They make the listeners feel something and want to do something. Depending on the context, this could be excitement that makes them want to invest, conviction that makes them want to spread the word, or passion that makes them want to campaign and make a difference. Getting the level of detail right is vital in comms. Too much information swamps the listener and buries the critical bits of information, and too little misses out what is important. The level of detail will vary according to the audience – do they want the Lambs' Tales from Shakespeare, or the story of King Lear? The right number of significant details gives the listeners, be they investors, journalists or healthcare professionals, enough to hold on to, and that might mean cutting favourite facts or slides. The presentation should end leaving people informed and wanting to act. Preparing the pitch Pitching is a fundamental part of the communications process, and it's important to be as Olympic fit as Princess Anne was in the London 2012 bid. As an Olympian, she was able to talk from a point of knowledge and experience. She presented what the International Olympic Committee needed to hear; that London was able to meet the needs of the games, and could put the logistics and infrastructure in place. A pitch must meet the client's needs, deal with any pain points, and be in the style that will be most useful. This could mean a traditional presentation, or a Q&A session. Reviewing the presentation from the client's perspective as well as the presenter's perspective can be useful, perhaps by putting a member of another team in the position of the client. This makes sure that it is written in the client's language, and helps to highlight anything that is missing. Moving virtual During the Covid-19 lockdown, meetings and pitches have quickly become virtual. This will continue as long as social distancing is in place, and may even become part of the post-virus 'new normal'. While virtual meetings allow life to continue, they do bring their own challenges. Virtual meetings do feel more 'real' than voice-only calls, but they can be exhausting. Fewer non-verbal cues and body language come across, and those that do can be harder to process, all of which takes more energy. If virtual meetings are going to become the way forward, all participants need to become comfortable with taking part. There are a number of ways to get the most out of virtual presentations:

I've been completing the COVID-19 Symptom Study app for some weeks now. This app, developed by King’s College London and health science company ZOE, has been created to combine symptom reports with software algorithms to try to predict who has the virus. This information can then be used to track SARS-CoV-2 infections across the UK and further afield. The study also looks at how symptoms and risks vary between individuals. I had reported headaches and chills over the weekend, which I think were the result of late nights doing coursework for my MA. The combination triggered an algorithm, inviting me to go for a PCR swab test to help the researchers to understand which symptoms are most related to Covid-19 infection. "You’ve recently reported feeling unwell with a particular combination of symptoms. We would like to test you to understand if you have the virus right now. This does not necessarily mean you have COVID-19 as we are also inviting some people we believe do not have the virus." I booked the test through the Department of Health website, which was a bit long-winded but pretty clear, and picked a site for a test, about a 40 minute drive away. I was a bit wary, as I know friends of mine have had bad experiences with the sites, and when I got close to Meadowhall I got a bit anxious, as there were no signs. I followed a stream of traffic, as I figured that SARS-CoV-2 testing was probably the only thing happening at the Meadowhall shopping centre that day, and from that point on it all went really smoothly and efficiently (until I left the site, took the wrong turning and ended up in an industrial estate, but that was my fault, not theirs). The site was staffed with soldiers in army fatigues and PPE, and as I pulled in, I was shown a sign telling me to keep my window shut unless otherwise told, and to show the QR code I got at registration. I then drove to the next point, where a very pleasant soldier handed me the test using a long-armed grab tool explained the process to me – I was to drive to a parking bay, swab my throat and then my nose, put the swab in the tube, label the tube lengthways with the bar code, and put it in the bag but not seal it. If I needed help, I should put my hazard lights on. I did the test as per the instructions, swabbing my tonsils (eww) and then pushing the swab up each nostril as far as I could and turning it (ouch). Not something I plan on doing again unless I must. I drove to the exit, where the soldier at the gate checked the bag contents and then told me to seal it, and then grabbed the bag with a long-armed grabber tool. I then drove to the gate, confidently turned right, turned round in the industrial estate and drove back past the testing site with my best 'I meant to do that' expression on my face. There are a couple of videos on the Department of health website that I found really useful – visiting a regional test site and How to take a coronavirus self-test swab. The results came by text within 48 hours and were negative, thankfully. I have added the result to the app. The app has led to some breakthroughs in information on Covid-19:

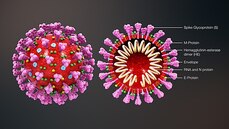

The researchers behind the app are also looking into the influence of hormones such as oestrogen in the responses to infection, and, as well as the effect of ACE inhibitors (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors) or ARBs (angiotensin receptor blockers) on the chance of infection.  This blog post is based on a conversation between Michael Watson, CEO of MEVOX and ex-president of Valera, Moderna's infectious disease spin-out, and the #CoffeeBuddies, a virtual discussion group hosted by Graham Combe and chaired by Professor Tony Sedgwick. Book to join #CoffeeBuddies on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 2.30 pm BST (GMT+1 hr) at Eventbrite. Since the first reported cases of a mysterious outbreak of viral pneumonia in Wuhan, China, in late December, the virus, now called SARS-CoV-2, hasn't been out of the news. Human to human transmission of the infection, known as Covid-19, was confirmed on 20 January 2020. As of 7 May 2020, there had been 3,843,153 reported cases and 265,657 reported deaths worldwide. The UK's daily confirmed Covid-19 deaths per million (rolling 7-day average) peaked at 13.89 per million on 15 April 2020, and had fallen to 8.37 per million on 7 May 2020. All about the virus Coronaviruses (from corona, Latin for crown or wreath) are RNA viruses with spike proteins studded all over their surface. Evolving alongside the amniotes (reptiles, birds and mammals), coronaviruses and have been around for millions of years. Coronaviruses were first identified in the 1960s, and SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans. A number of coronaviruses, including B814, 229E and OC43, cause around 15% of common colds. While the new virus' origin is still not clear, it appears to be closely related to bat and pangolin viruses. There have been a number of coronavirus outbreaks over the last two decades, including the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV-1) outbreak in China and Hong Kong in 2003, and the MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV) in 2012. The pandemic in 1889-1890, which resulted in one million deaths, may have been caused by HCoV-OC43 jumping from cows to humans. SARS-CoV-2's spike proteins bind with the human ACE2 receptor, found in lungs, kidney, heart and gut. This ties in with the symptoms of Covid-19, which include fever, cough, shortness of breath, and diarrhoea, and can worsen to cause strokes and kidney failure. Letting go of the tiger's tail Modelling from Neil Ferguson and the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team suggested that, if nothing was done to mitigate the epidemic in the UK, critical care bed capacity would be exceeded in the second week of April, and deaths would peak at around 500,000 in May or June. Controlling the tiger that is Covid-19 requires primary and secondary prevention, allied with primary and secondary treatment approaches:

The UK went into lockdown on 23 March 2020. The UK government is discussing when and how lockdown will ease, and what social intervention will look like in the future. Between the current peak and a potential secondary peak of infection as lockdown eases is a critical and narrow window for vaccine and therapeutic development. Highly effective contact tracing and case isolation could also be important in controlling new outbreaks. Antivirals could play a role in treatment A study of Gilead's remdesivir in 1063 hospitalized adults showed a 31% faster time to recovery in treated patients compared with placebo (p<0.001), reducing the median time for recovery to 11 days compared with 15 days. The mortality rate in treated patients was 8.0% compared with 11.6% in the placebo group (p=0.059). Remdesivir has been studied in Ebola virus disease, MERS and SARS caused by SARS-CoV-1 infection. Designing a vaccine for primary prevention A safe and effective vaccine will be the best way out of the current pandemic, as waiting for herd immunity would require between 60% and 80% infection in the population, with a lot of suffering and death over several years. There are over 125 Covid-19 vaccine candidates in the pipeline to date, with eight or nine in the clinic. This is expected to increase to over 25 in the clinic by the end of 2020. Approaches include nucleic acid vaccines (mRNA, DNA),inactivated or live attenuated vaccines, or viral vectored vaccines. Normally vaccine development takes over 10 years, but this outbreak has seen vaccines developed to clinical stage in record time. Each vaccine approach has its benefits and its challenges:

Another positive for the development of a vaccine – while coronaviruses do continue to mutate, they have an RNA 'proofreading machine' that slows the evolution of the virus. According to data published on 4 May 2020, there have been relatively few mutations spotted to date. Provided clinical trials can show a 'good enough' protection from an initial dose, or dose + booster, the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may need to be given annually, much like the influenza vaccine. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed